Polyvagal theory in psychotherapy offers co-regulation as an interactive process that engages the social nervous systems of both therapist and client. Social engagement provides experiences of mutuality and reciprocity in which we are open to receiving another person, as they are. For the client who was rejected in childhood, this moment of being received can be profoundly reparative.

Before offering any interventions aimed toward regulation, develop your understanding of the client’s current experience within the context of their developmental, social, and cultural history. For example, if they are angry, firmly validate why this anger makes sense in the context of their experiences in the world. Explore how it feels to nonjudgmentally accept them and yourself just as you are.

“The goal of regulating emotions is not to make feelings go away. Rather, the aim is to help clients build their capacity to ride the waves of big emotions and sensations. Initially, this occurs because they know that we are willing to join them in these difficult moments. In time, this process helps them learn that temporary experiences of contraction can resolve into a natural expansion of positive emotions such as relief, gratitude, empowerment, or joy.”

Dr. Arielle Schwartz

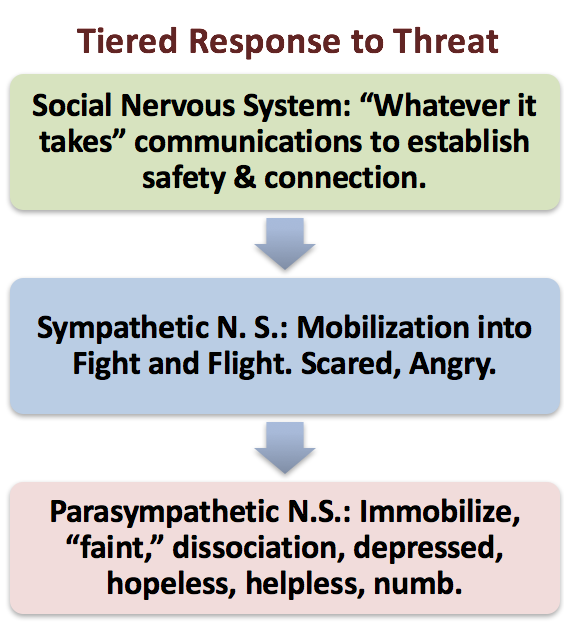

As human beings, we are equipped with built-in protective mechanisms that helps us survive threatening situations. When we experience a threat, we mobilize into self-protection through the sympathetic nervous system. Just as animals seek to flee or fight a predator; we too, might rely upon these defense mechanisms to survive. However, when there is no way to escape an ongoing threat, we may might immobilize into stillness through the parasympathetic nervous system as a form of self-protection. We can see this “feigned death” in animals who stop moving or faint in hopes that a predator will lose interest in them.

Initially, it was believed that the parasympathetic was only associated with the nourishing and regenerative effects of relaxation and digestion. However, we now realize that the parasympathetic nervous system has two presentations depending upon whether we feel safe or threatened. In times of safety, the parasympathetic nervous system facilitates the classically understood regenerative responses of rest and digest. In times of threat the parasympathetic nervous system has a defensive mode which is associated with immobilization into collapse, helplessness, and a feigned death or “faint” response in the body.

Dr. Stephen Porges’ polyvagal theory illuminates two circuits of the vagus nerve. We have a more recently evolved vagal circuit called the “ventral vagal complex” (VVC), also called the “social nervous system” which helps us to feel safely connected to others. The social nervous system is the part of the vagus nerve that helps us feel socially connected and safe in the world. Additionally, we have an evolutionarily older circuit called the “dorsal vagal complex” (DVC) which is responsible for defensive immobilization.

When we feel threatened, we will typically will move through a sequence of three autonomic nervous system pathways; each aimed for survival. When possible, we will first try to engage our “social nervous system” to re-establish a sense of connection and safety. For example, a child who is facing separation from his or her mother might initially try to smile or reach out for mommy’s hand for reassurance or to prevent her departure.

However, if the child is unable to secure a safe, relational bond, he or she will begin to cry or cling. This might evolve into feelings of fear or anger which may be seen as the child runs away or begins to hit mommy. These behaviors indicate that the child has mobilized into fight and flight through sympathetic nervous system activation. In situations of ongoing threat such as when a child is being abused or when a person is held in captivity then fight or flight may not help the individual establish safety. In this case, the individual will rely upon the evolutionarily older expression of the Dorsal Vagal Circuit which is characterized by immobilization into collapse, loss of muscle tone, slowed heart rate, nausea, dizziness, and numbness.

Porges offers the term “neuroception” to account for the ways in which our nervous system responds to internal and external cues of safety or danger. Moreover, he explains that this happens without our conscious awareness. For example, a woman who had been violently attacked was having difficulty going to baseball games many months later. She experienced tremendous at these events and didn’t realize why. However, in therapy she recalled that the man who attacked her was wearing a baseball cap. Her body had been responding to the trigger of the hat without realizing why.

Importantly, it is possible to increase our conscious perceptions of nervous system changes such as an increase in heart rate, postural collapse, or changes in how we are breathing. Doing so can help us to notice the level of arousal of our autonomic nervous system, become curious about why we are feeling keyed-up or shut down, and respond in a manner that increases a sense of safety and connection.

When we as therapists attune to our own embodied awareness during sessions, we can sense subtle changes in our own somatic awareness that might provide insight into the experience of the client. For example, you might notice a subtle tightening in your chest and, as a result, place your hand over your heart and take a deep breath. By attuning to your own body, youmodel your own regulation. This can then become a nonverbal invitation for the client to breathe more deeply. Or, we might use this information to encourage clients to sense their body and breath.

In her book, The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy, Deb Dana (Dana, 2018) explores co-regulation as an interactive process that engages the social nervous systems of both therapist and client. It is common for clients with trauma, especially those with Complex PTSD, to alternate between hyper-arousal and hypo-arousal states. However, we can help them to feel safe and connected; even in the midst of difficult emotions and body sensations. Co-regulation requires that we, as therapists, are comfortable with a wide range of affect and arousal states. Clients with developmental trauma may have never had another person who was able to be with them in their distress without becoming anxious themselves, shutting down, or leaving them in the midst of their pain.

Applying polyvagal theory in psychotherapy involves engaging the social nervous system in ourselves and our clients. Importantly, engagement of the social nervous system is not the same as simply offering “support.” Rather, engagement offers an experience of mutuality and reciprocity in which we are open to receiving them, as they are. When we, as therapists, offer our openness and receptivity to clients, they feel accepted and understood.

Within somatic psychology, therapists are encouraged to pay attention to their own sensations as opportunities for transformational moments in therapy. For example, you might share a momentary heaviness in your chest and accompanying sadness in response to a client’s experience. This communicates that you have been moved or changed by your client. For the client who was rejected in childhood, this moment of being received can be profoundly reparative. You have let them know that they are important, their presence is felt, and they make a difference—because they have had an impact on you.

Polyvagal theory in psychotherapy is based in a relational model which recognizes that we all make mistakes sometimes. We will inevitably misunderstand our clients, look at the clock at the wrong time, or say something inadvertently hurtful. We are all human, are we not? Small ruptures in therapy can offer opportunities for repair. Acknowledgement of these vulnerable moments can offer a contrast to experiences of childhood in which relational ruptures were never addressed.

When a client grew up with a primary caregiver who was disengaged and unavailable; their needs to be accepted, loved, and understood were neglected. Furthermore, if there was ongoing abuse, there may have been no way to escape a dangerous situation. When caregivers were dysregulated themselves, the client may have experienced intensely disrupted states for extended periods of time.

Additionally, a buildup of poorly attuned moments in therapy can result in feelings of confusion, frustration, or disconnection. Both therapist and client might play out injurious patterns from each of their past, which can impair the client’s trust in the therapist. If as therapists, we do not take the time to understand our own countertransference, we might engage in behaviors that inadvertently push our clients away or lead them to feel rejected. For example, our discomfort might be communicated nonverbally through our body language such as unconsciously angling our torso away from a client or carrying tension in our voice tone. Unfortunately, the accumulations of micro-aggressions can lead to the loss of faith in therapy over time.

Through personal introspection, supervision, or therapy, we can increase self-knowledge of our own attachment histories and relational learnings. These dynamics can become catalysts for us to attend to the wounds from our own past. When we take responsibility for our part in the dynamic, we have an opportunity to repair moments of disconnection and restore our client’s trust in us. Relational ruptures followed by repair helps us all to recognize that interpersonal conflicts can be resolved. We learn that we are capable of navigating our way through challenging experiences of disconnection. Ultimately, we learn that we can handle these stressors and come out stronger.

Jessica came into therapy as a strong and capable woman in her fifties. She was accomplished and a hard worker; although, she had a tendency to hold herself to unrealistically high standards. At times, this manifested as a strong self-critic and perfectionism. She struggled in her relationships and described feeling exasperated by others inadequacies. Nonetheless, she had a tenacious capacity to keep an optimistic attitude. She rationalized all the reasons why the hardships in her life were for the best. Initially, Jessica would begin therapy appointments by telling me about her accomplishments or talking about positive moments from her week.

Her upright posture and bright smile were uplifting and contagious. I felt compelled to commend her for accomplishments. However, toward the end of many of our sessions her affect would abruptly change. She would suddenly announce that she was not getting her needs met in therapy. The warm smile on her face was replaced by a cold, distant, and aggravated expression as she proceeded to tell me of all the ways that I had disappointed her.

As we deepened our work together, we began to explore Jessica’s childhood. I learned that her mother was only 20 when Jessica was born and would often talk about how she hadn’t wanted a pregnancy that early in her life. Her mother would tell friends about how Jessica had “taught herself to walk by 9 months, potty-trained herself by a year, and how after that, she was on her own.” Those words, “she was on her own” captured the wound that Jessica carried with her into adulthood. In other words, Jessica was taught not to have needs. Moreover, she learned there was no place for painful emotions of sadness, hurt, jealousy, or anger. Instead, Jessica became mommy’s little helper and was rewarded for her competence, self-reliance, and ability to care for her two younger sisters. By the time she was 16, Jessica was relatively independent. She worked two jobs, made her own clothes, continued to help around the house, and drove her siblings to school. While her self-reliance helped her to survive, it also covered up her underlying unmet needs for care, tenderness, affection, and understanding.

Despite this deepened understanding of Jessica’s attachment history, I continued to feel my own anxiety build as I anticipated the painful moments in sessions when she would become critical of me. In supervision, I explored my fear of her becoming angry with me. I identified how this feeling was reminiscent of wounds from my own childhood. I recalled memories of myself as a little girl who had to be good in order to avoid being the target of criticism. I never knew when I had done something wrong; when one of my parents would be angry with me. I could see how my history had some similar elements to Jessica’s history. This realization also helped me to understand how my fears had led me to avoid Jessica’s feelings of anger, hurt, and disappointment.

In the next session, I began by offering my understanding about how Jessica’s need to be the “strong one” for so much of her life left little space for her feelings of hurt and anger. I also acknowledged how I had not sufficiently attended to her distress in our work together. Jessica sighed in relief, as she could feel that there was more room for her feelings. I let her know that it was okay for her to be angry with me. This statement offered an important repair; especially, considering that she was never able to express her anger toward her mother.

This session was a turning point in our work together. The dynamic did not continue to play out between the two of us as we were able to create a safe place to attend to a wide range of her feelings. She shared how grateful she was to have a place where could express anything she needed and gave a small poster that remains on my desk to this day, which states “Everything is welcome here: your pain, your sadness, your shame, your guilt, your anger, your grief, your joy.” She now knew, that her painful experiences and her phenomenal strengths were all welcome in the room.

Applying polyvagal theory in psychotherapy involves asks us to accept clients (and ourselves) as they (and we) are. This foundation of acceptance is the ground from which change and growth is possible. The result is an atmosphere of compassion that is mutually nourishing. We too, have an opportunity to grow; we can be changed for the better through our work with our clients.

The Complex PTSD Treatment Manual: An Integrative Mind-Body Approach to Trauma Recovery is written for clinicians who are helping clients navigate the consequences of repeated or chronic traumatization. This is a roadmap for therapy with clients who have experienced prolonged and chronic exposure to traumatic events.

This book offers a deep dive into the ways in which therapy is a combination of head and heart, of science and art. A mind-body approach to trauma recovery is now recognized as essential to successful treatment for we simply cannot think our way out of these innate, physiological responses to trauma. Successful treatment requires a compassionate therapeutic relationship and effective, research-based interventions. This integrative model brings together relational therapy, mindful body awareness, parts work therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), somatic psychology, and practices drawn from complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Click Here to order.

Within The Post Traumatic Growth Guidebook, you will find an invitation to see yourself as the hero or heroine of your own life journey. A hero’s journey involves walking into the darkness on a quest for wholeness. This interactive format calls for journaling and self-reflection, with practices that guide you beyond the pain of your past and help you discover a sense of meaning and purpose in your life. Successful navigation of a hero’s journey provides opportunities to discover that you are more powerful than you had previously realized. Click here to order the book on Amazon.

In The Complex PTSD Workbook, you’ll learn all about Complex PTSD Recovery and gain valuable insight into the types of symptoms associated with unresolved childhood trauma, while applying a strength-based perspective to integrate positive beliefs and behaviors. This is a great add-on with the Post Traumatic Growth Guidebook…Click here to order.

As a compliment to the Complex PTSD Workbook, A Practical Guide to Complex PTSD: Compassionate Strategies for Childhood Trauma, is meant to provide compassionate support for the process of healing from childhood trauma. You can think of it as a lantern that will illuminate the dark spaces and provide a sense of hope in moments of despair. The practical strategies you will learn in this book are taken from the most effective therapeutic interventions for trauma recovery. You will learn the skills to improve your physical and mental health by attending to the painful wounds from your past without feeling flooded with overwhelming emotion. My wish is to help you discover a new sense of freedom. The traumatic events of your past no longer need to interfere with your ability to live a meaningful and satisfying life. Click here to Order on Amazon.

For therapists, The EMDR Therapy and Somatic Psychology book, teaches you how to integrate two of the best known trauma recovery modalities into your practice. Click to order it here and increase your toolbox for healing using this integrative and effective approach to healing.

Dr. Arielle Schwartz is a licensed clinical psychologist, wife, and mother in Boulder, CO. She offers trainings for therapists, maintains a private practice, and has passions for the outdoors, yoga, and writing. She is the developer of Resilience-Informed Therapy which applies research on trauma recovery to form a strength-based, trauma treatment model that includes Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), somatic (body-centered) psychology and time-tested relational psychotherapy. Like Dr. Arielle Schwartz on Facebook,follow her on Linkedin and sign up for email updates to stay up to date with all her posts. Dr. Schwartz is the author of four books:

Image Credits: Ryan McGuire and Pezibear on Pixabay

Arielle Schwartz, PhD, is a psychologist, internationally sought-out teacher, yoga instructor, and leading voice in the healing of PTSD and complex trauma. She is the author of five books, including The Complex PTSD Workbook, EMDR Therapy and Somatic Psychology, and The Post Traumatic Growth Guidebook.

Dr. Schwartz is an accomplished teacher who guides therapists in the application of EMDR, somatic psychology, parts work therapy, and mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of trauma and complex PTSD. She guides you through a personal journey of healing in her Sounds True audio program, Trauma Recovery.

She has a depth of understanding, passion, kindness, compassion, joy, and a succinct way of speaking about very complex topics. She is the founder of the Center for Resilience Informed Therapy in Boulder, Colorado where she maintains a private practice providing psychotherapy, supervision, and consultation. Dr. Schwartz believes that that the journey of trauma recovery is an awakening of the spiritual heart.