Many mental health practitioners are trained in the treatment of single traumatic events. However, in the case of complex trauma and dissociative symptoms, clients come to therapy with an extensive history of trauma that often begins in childhood and continues into adulthood with layers of personal, relational, societal, or cultural losses. Clients arrive at the door with profoundly painful histories and well-constructed defense structures to protect themselves from the pain.

Complex PTSD and dissociative symptoms can arise as a result of repeated developmental trauma or neglect and the ongoing social stress such as bullying, discrimination, political violence, or the distress of being a refugee separated from family and country.

“A compassionate approach to treatment understands that dissociation is a learned behavior that once helped the client survive and cope with a threatening environment. Dissociation is a both a built-in physiological survival mechanism and a psychological defense structure. It helps the individual to disconnect from the reality of threatening experiences. However, over time, dissociation can become a well-maintained, dysfunctional division between the part of the self that is trying to live a “normal life” and the part of self that is holding trauma related material.”

-Dr. Arielle Schwartz

Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) fall into three categories: re-experiencing, heightened arousal symptoms, and avoidance. Re-experiencing can occur as intrusive memories or sensations, flashbacks, or nightmares. Symptoms of heightened arousal includes anxiety, feelings of panic, and hypervigilance in which the client feels as though they must remain on guard or highly sensitized to the environment or people’s body language. Avoidance symptoms including changing behaviors to avoid exposure to external or internal reminders of the trauma.

In order to avoid an external reminder of trauma, the client might avoid going certain places that are associated with the traumatic event. However, avoidance of internal reminders often involves behaviors that serve to suppress or detach from uncomfortable sensations, emotions, and memories.

PTSD has typically been associated with hyperarousal, increased limbic arousal, decreased prefrontal lobe activity, increased sympathetic nervous system arousal, and elevated levels of cortisol in the bloodstream leading to elevated heart rate and respiration. There is also a dissociative subtype to the PTSD diagnosis that tends to occur when traumatic events are particularly severe. In contrast to the traditional PTSD diagnosis, the dissociative subtype is distinguished by hypoarousal and emotional detachment. Here, the client might describe feeling disconnected from their body, as if the body isn’t part of them, as if the world around them isn’t real, difficulty remembering details about the traumatic event, or as if they are living in a daze (that is not medication induced). These symptoms are referred to as derealization and depersonalization.

Complex PTSD occurs as a result of ongoing trauma that arises due to chronic neglect, abuse, exposure to domestic violence, prolonged captivity, bullying, discrimination, community or political violence, and the distress of being a refugee separated from family and country. The diagnostic criteria for Complex PTSD includes re-experiencing, avoidance, and heightened arousal symptoms as well as three additional categories of symptoms including difficulties with affect regulation, disturbances with self-organization, and interpersonal problems.

Hypervigilance within Complex PTSD may present as being highly sensitized people’s body language, facial expressions, and voice tone. Difficulties with affect regulation can come in the form of high arousal emotions such as anxiety, rage, or fear and low arousal emotions such as helplessness, hopelessness, despair, and depression. Avoidance symptoms experienced by individuals with Complex PTSD might present as denying any disturbance related to childhood, idealizing parents, repressing feelings, minimizing the pain, or dissociating as a way to avoid feeling distressing emotions or sensations now.

According to Christine Ford (2009), children undergo a “biological trade-off” when they grow up in a home where there is ongoing neglect or repeated frightening and abusive events. This trade-off leads them to forgo their natural inclination for learning, curiosity, growth and self-development for the sake of survival. Over time, this can lead the child and later, the adult, to sacrifice exposure to enriching new experiences for the sake of maintaining a pseudo-safety. Even in the absence of violent or sexual attacks on the body, ongoing emotional abuse that involves psychological attacks, shaming, rejection, or neglect has the ability to damage the integrity of the self-identity of the child. These “invisible” traumatic events are also associated with a loss of self-regulatory abilities including impulsivity and reactivity to stress (Teicher et al., 2006).

Sometimes it can be difficult to form an accurate diagnosis of Complex PTSD. In part, this is because traumatic family dynamics or events can become “normal” for a child. This distorted world was the only world known to the child. Furthermore, children are dependent upon their caregivers and will form attachments; even if this is an attachment to the parents or caregivers who were the source of terror. In other words, the child acclimates to a dangerous world from which there is no escape. To the best of their ability, a child will make a dangerous environment tolerable; even if this is accomplished by fantasy alone. Sometimes this process involves creating an idealized mommy or daddy within the mind and dissociating from the reality of the external world. This can result in a deep fracture within the structure of the organization of the self.

Children also tend to develop inaccurate beliefs about themselves as a way to cope with the uncontrollable outer world. They might conclude that “There is something wrong with me,” “It’s all my fault,” or “I do not deserve to exist.” This process displaces the blame of the abuse or neglect onto the self. Perhaps, these thoughts arise because there is more control when a child believes that they are the source of the problem. Furthermore, as Dr. Jim Knipe (2018) suggests, it is utterly unfathomable for a child to contemplate that they are a good kid relying upon bad parents. Therefore, it is actually safer to believe that they are a bad child, relying upon good parents. Such compromised meaning making is a dominant symptom of Complex PTSD.

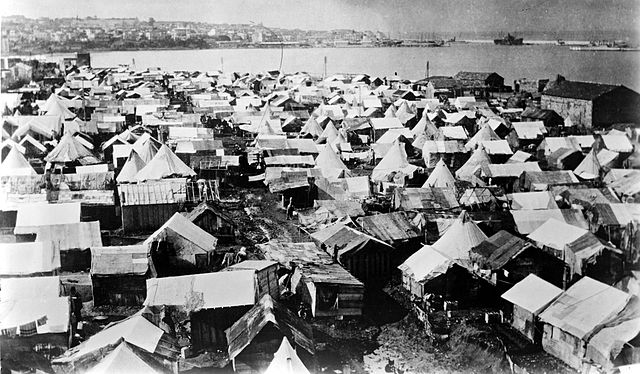

In some cases, Complex PTSD can arise in adulthood is the result of prolonged violence or captivity and ongoing oppression, prejudice, or discrimination. Some individuals may have suffered from political imprisonment, torture, or untenable refugee situations separating them from family or country. They may have faced or be currently facing the chronic stress of uncertainty, the ongoing threat of deportation, poverty, disability, or a persistent lack of a sense of social belonging.

These profoundly damaging experiences can drastically impact the ability to trust other people or the world at large. Individuals may have faced profound helplessness and powerlessness that leads to a depletion of mental and emotional resources. It can feel nearly impossible to retain a sense of being a person or trusting that your actions will make a difference in the outcome your life.

Upper brain centers such as the prefrontal cortex play an inhibitory and down-regulating role in limbic activation. Within the limbic system lies a small, almond-shaped structure implicated in traumatic memory called the amygdala. During traumatic events, the amygdala is responsible for storing strong fear-based sensory fragments of memories. Specific details such as smells, sounds, and felt experiences can be strongly imprinted and vividly recalled.

Simply put, being triggered into a trauma response can lead to suppression of the upper brain centers which increases the likelihood of feeling flooding by re-experiencing symptoms. Cognitive tasks engage upper brain centers and reduce activity in limbic regions. However, childhood trauma can lead to impairments in the upper brain centers leaving the individual more vulnerable to becoming emotionally flooded (Teicher et al., 2016).

Paradoxically, too much activation in upper brain can also be detrimental to mental health. Brain scans indicated increased prefrontal lobe activity and increased connections from upper brain to midbrain centers among individuals with dissociative symptoms (Felmingham et al., 2008; Nicholson et al., 2017). This finding aligns itself with the dissociative subtype of PTSD in which individuals experience a predominance of dissociative symptoms and hypoarousal. This dissociative subtype seems to be a result of the inhibition of limbic regions, reduced sensory awareness, and parasympathetic nervous system dominance (Lanius, et al., 2012). Simply put, an overmodulation of arousal can lead an individual to feel detached and disconnected from their emotions and sensations.

When working with clients with dissociative symptoms, it is helpful to understand the individual within the context of their developmental, social, and cultural history. With an understanding of the historical traumatic events, we can better understand the current triggers for disturbing symptoms.

Often, dissociative symptoms are triggered by recent events involving relational losses or perceived threats that are reminiscent of historical traumatic wounds. Sometimes, by the time the client arrives at the appointment, they have been in a state of overwhelm or shut-down for many days. Initially, clients might not realize why they disconnected from their feelings and themselves. However, as we review the trajectory of recent events, we can usually develop a mutual understanding of the experience that triggered the dissociative episode.

For example, a client came in feeling emotionally cut-off and shut-down. She had difficulty making eye contact. She was visibly collapsed and said that she went to the place of “nothingness.” Without judgment, I acknowledged her experience. Slowly, I began to inquire if an event might have triggered the dissociation she shrugged her shoulders and said, “I guess so, I did have a fight with my husband.” The simple invitation, “tell me more about the fight” opened her up to some of the feelings which had been too much to handle at the time. She said, “It was a bad one, we were both so triggered. We said things that we both regret. I think he’s really going to leave me this time, I’m just too much of a burden with all of my trauma. I’m just too complicated to love!” Looking back, we discover that after the argument with her husband she had a few drinks because she didn’t have the resources to cope with the distress. She woke up the next day feeling foggy and tired. Now, she felt numb.

Since we had already discussed her developmental history, I knew she had experienced ongoing rejection by her mother and abandonment by her father when she was a young child. I was able to hold her fear of being left by her husband within this context and together we tuned into the young part of her that experienced these losses. Slowly, with compassion, we made space for the part of her that felt like a burden to feel included, here and now. She began to look around the office and eventually she made eye contact with me. I said, “Right now, you are not rejecting this young part of you.” She acknowledged that she felt safe now. I asked how things were with her husband since the fight. She said, “He’s actually been really nice to me but I have been pushing him away. I’ve been holding the fight against him. When I dissociated, I was also shutting him out. I can stop doing that now.”

It is possible to heal from Complex PTSD and dissociative symptoms. However, keep in mind that these symptoms are often the result of traumatic injuries that occurred over an extended period of time and that influence the identity of the individual. Therefore, it is important to remain realistic about the timeline of healing and to work at a tolerable pace for their healing journey. Each relational moment of compassion might feel “invisible;” however, these meaningful moments are the building blocks of a foundation for a revised, healthy sense of self.

Photo Credits: Arielle Schwartz, D. Sharon Pruitt, Bain/Library of Congress

The Complex PTSD Treatment Manual: An Integrative Mind-Body Approach to Trauma Recovery is written for clinicians who are helping clients navigate the consequences of repeated or chronic traumatization. This is a roadmap for therapy with clients who have experienced prolonged and chronic exposure to traumatic events.

This book offers a deep dive into the ways in which therapy is a combination of head and heart, of science and art. A mind-body approach to trauma recovery is now recognized as essential to successful treatment for we simply cannot think our way out of these innate, physiological responses to trauma. Successful treatment requires a compassionate therapeutic relationship and effective, research-based interventions. This integrative model brings together relational therapy, mindful body awareness, parts work therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), somatic psychology, and practices drawn from complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Click Here to order.

A Practical Guide to Complex PTSD: Compassionate Strategies for Childhood Trauma, which is meant to provide compassionate support for the process of healing from childhood trauma. You can think of it as a lantern that will illuminate the dark spaces and provide a sense of hope in moments of despair. The practical strategies you will learn in this book are taken from the most effective therapeutic interventions for trauma recovery. You will learn the skills to improve your physical and mental health by attending to the painful wounds from your past without feeling flooded with overwhelming emotion. My wish is to help you discover a new sense of freedom. The traumatic events of your past no longer need to interfere with your ability to live a meaningful and satisfying life. Click here to Order on Amazon.

Read The Post Traumatic Growth Guidebook: Practical Mind-Body Tools to Heal Trauma, Foster Resilience, and Awaken your Potential. Within the pages of this book, you will find an invitation to see yourself as the hero or heroine of your own life journey. A hero’s journey involves walking into the darkness on a quest for wholeness. This interactive format calls for journaling and self-reflection, with practices that guide you beyond the pain of your past and help you discover a sense of meaning and purpose in your life. Successful navigation of a hero’s journey provides opportunities to discover that you are more powerful than you had previously realized. Click here to order the book on Amazon.

Want to learn more about healing PTSD?

Connect to this post? The EMDR Therapy and Somatic Psychology book, is available on Amazon! Click here to increase your toolbox for healing. An integrative and effective approach to healing from trauma.

The Complex PTSD Workbook is available on Amazon! Click here to check it out.

Dr. Arielle Schwartz is a licensed clinical psychologist, wife, and mother in Boulder, CO. She offers trainings for therapists, maintains a private practice, and has passions for the outdoors, yoga, and writing. She is the developer of Resilience-Informed Therapy which applies research on trauma recovery to form a strength-based, trauma treatment model that includes Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), somatic (body-centered) psychology and time-tested relational psychotherapy. Like Dr. Arielle Schwartz on Facebook, follow her on Linkedin and sign up for email updates to stay up to date with all her posts.

Arielle Schwartz, PhD, is a psychologist, internationally sought-out teacher, yoga instructor, and leading voice in the healing of PTSD and complex trauma. She is the author of five books, including The Complex PTSD Workbook, EMDR Therapy and Somatic Psychology, and The Post Traumatic Growth Guidebook.

Dr. Schwartz is an accomplished teacher who guides therapists in the application of EMDR, somatic psychology, parts work therapy, and mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of trauma and complex PTSD. She guides you through a personal journey of healing in her Sounds True audio program, Trauma Recovery.

She has a depth of understanding, passion, kindness, compassion, joy, and a succinct way of speaking about very complex topics. She is the founder of the Center for Resilience Informed Therapy in Boulder, Colorado where she maintains a private practice providing psychotherapy, supervision, and consultation. Dr. Schwartz believes that that the journey of trauma recovery is an awakening of the spiritual heart.