Vagus nerve yoga for trauma recovery integrates information from neuroscience, psychology, and the yogic path to illuminate who we are and how we heal from adverse and challenging life events. This post applies Dr. Stephen Porges’s polyvagal theory to illuminate the physiological underpinnings of how we, as humans, respond to stressful or traumatic events.

Read on and learn how you can fine-tune your health with yogic breath, movement, and awareness practices which can become building blocks for a life-changing daily practice.

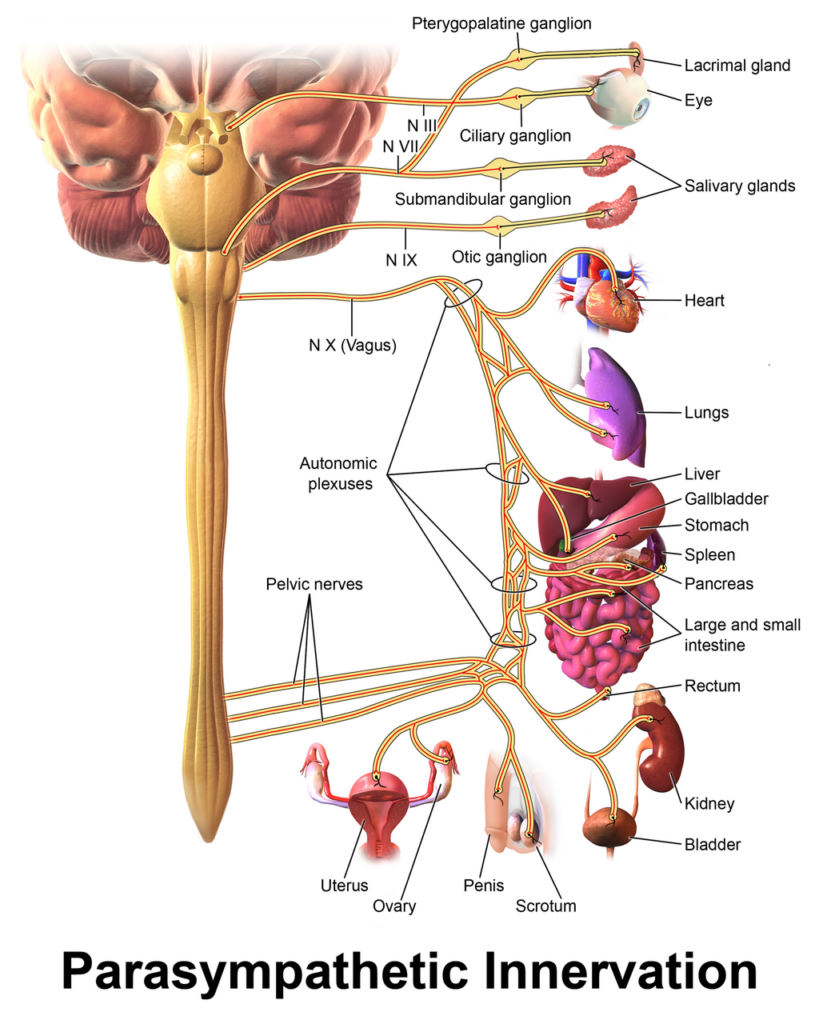

The vagus nerve plays a central role in your emotional and physical health. The term vagus is Latin for “wandering,” an apt descriptor as this nerve extends from the brainstem down into your stomach and intestines, innervates your heart and lungs, and connects upward into your throat and facial muscles.You can think of the vagus nerve as a bi-directional communication system helping you stay in touch with your sensations and emotions.

The vagus nerve plays a key role in your body’s second or enteric brain that exists within your gastrointestinal system. Nerve fibers within your stomach and intestines not only regulate digestion, peristalsis, and elimination; but also produce the same neurotransmitters found in the brain. Your gut is capable of responding to stress even before you have consciously registered a trigger. By then, stress chemicals may already have been communicated between your digestive system and your brain through the vagus nerve.

The nervous system is constantly scanning for cues to determine whether situations or people are safe, dangerous, or life threatening. Unconsciously, we are looking for these cues within our own body, in the environment around us, and in the body language, facial expressions, or voice tones or other people. Without realizing it, your belly constricts, heart rate increases, and muscles in your arms or legs grow tense. You might be reacting to the sound of your partner’s voice, a smell of cologne, or the look on a stranger’s face.

Approximately 80% of vagus nerve fibers travel from the body to your brain. This explains why we cannot think our way out of trauma reactivity; rather, we must work with the body to maximize healing.

The polyvagal theory recognizes that the vagus nerve has two circuits. The most recently evolved circuit is called the ventral vagal complex or social engagement systembecause it connects area of that body that are primarily involved in helping us feel socially connected and safe in the world.

We also have an evolutionarily older circuit of the vagus nerve called the dorsal vagal complex which connects to our digestive organs. When we feel safe, the ventral vagal and dorsal vagal circuits work together to facilitate our “rest and digest” response. However, when we experience a threat, and we are unable to restore a sense of safety then the dorsal vagal complex initiates a primitive defensive response of immobilization in which our heart rate slows down, we lose muscle tone, and we might feel nauseous, dizzy, or numb.

The sympathetic nervous system is our stress response system. This engages to help us fight or flee from a dangerous situation. Both the ventral and dorsal vagal branches engage the parasympathetic nervous system which inhibits the sympathetic nervous system. If you think of your sympathetic nervous system as a metaphorical gas pedal, both branches of the vagus nerve function as a metaphorical “brake.”

The ventral vagal complex allows you to slow down in a smooth, restful manner; whereas, the dorsal vagal is an abrupt brake that can lead you to feel collapsed and immobilized. In some cases, you might feel as though you are alternating rapidly between both nervous system states; as if you aredriving with one foot on the gas and one foot on the brakes.

Your social engagement system allows you flexibly adapt to stress as it helps you to feel calm, connected, and capable in choosing how to respond to a range of feelings and experiences. You can awaken your ventral vagus nerve by breathing into your belly with long, slow exhales or by humming to create a gentle vibration in your throat and ears. You can also explore releasing tight muscles in your neck that inhibit blood flow to your vagus nerve. Or, you might move your spine rhythmically from a seated or table top position which can enhance a feeling of freedom and connection throughout your body.

Once you are connected to your social engagement system, you can blend this nervous system resource with your sympathetic nervous system helps you connect to joy, excitement, play, and laughter. On the yoga mat, this blend can help you to mobilize your body into active postures such as downward dog, lunges, standing postures, and heart openers.

You can also blend your social engagement system with the dorsal vagal complex which allows you find nourishment in states of stillness and deep relaxation. On the yoga mat, this blend can help you to soften into restorative poses such as child’s pose, yoga nidra, or the deep spiritual states found in meditation.

Our experience of embodiment is a combination of three sensory systems: exteroception, interoception, and proprioception.

Dr. Porges coined the term neuroception to reflect the process by which the autonomic nervous system scans for and responds to internal and external cues of threat. When engaging in neuroception, you can begin to consciously observe for signs that your body is responding to a perceived threat in our body. Here are some examples of what you might notice:

You have an opportunity to practice sensory and neuroceptive awareness every time that you engage in a yoga practice. Once you increase your perception of any signs of threat in your body, you can then begin to discern whether the autonomic response you are having is a reflection of an area in your present-day life that is leading you to feel unsafe. If indeed, you are in a situation that feels threatening, you can best determine a course of actions that help you to protect yourself.

Conversely, you might recognize that there is no current threat—now, you know that you’re defensive response is a remnant from the past. In this case, you can explore letting go of unnecessary defensive reaction by finding a yoga posture that helps release emotional tension or by connecting to your breath in a way that helps calm down your nervous system.

From a yogic perspective, the root cause of our suffering is not knowing the truth of who we are. Within Indian philosophy, the work Sanskrit word jnana, translated as self-knowledge, is used to reflect the underlying purpose of all yoga practices which is to facilitate self-realization. The Sanskrit word jnana and the English word know both have etymological roots in the Greek word gnosis.

You cultivate jnana or self-knowledge in vagus nerve yoga for trauma recovery by observing your own nervous system states so that you may recognize signs of imbalances. Now, you can respond in a caring manner that enhances your wellness.

On the yoga mat, this process involves learning to listen carefully to the wisdom of your body. Every time you engage in a yoga practice offers an opportunity to check in and notice your body so that you can adapt your practice to meet your changing needs. Each practice will be new and different. How you feel at the beginning of a practice inevitably changes and evolves. Simply be present with whatever arises. The practice can then become a conversation with your body in a way that allows you to transform and grow.

Yoga practices can help you release the impact of historical events and triggering situations. Animals in the wild who rely upon the dorsal vagal faint response tend to shake or engage in a flight response to release this state of defensive immobilization. We too can move out of a collapsed or shut down state through mindful engagement of the sympathetic nervous system through movement. Deb Dana refers to this process as climbing the polyvagal ladder from a feeling of unease to an experience of safety and connection to others (Dana, 2018).

This ten minute video offers a short vagus nerve yoga for trauma release recovery focused on awakening instinct and intuition. I invite you to explore this practice gently and lovingly. Meet yourself where you are. Most important to any yoga practice is that you know that you have choices. For example, you can keep your eyes open or closed and you can explore how you want to breathe in any shape. Remember, the outer look of any posture is not our goal. Rather, you have permission to adapt and change how you move your body at any time.

This post has excerpts from the book, Therapeutic Yoga for Trauma Recovery,

This book introduces you to the power of the yogic philosophy and offers a variety of accessible yoga poses and breathing practices that will allow you to:

Dr. Arielle Schwartz is a licensed clinical psychologist, wife, and mother in Boulder, CO. She offers trainings for therapists, maintains a private practice, and has passions for the outdoors, yoga, and writing. She is the developer of Resilience-Informed Therapy which applies research on trauma recovery to form a strength-based, trauma treatment model that includes Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), somatic (body-centered) psychology and time-tested relational psychotherapy. Like Dr. Arielle Schwartz on Facebook, follow her on Linkedin and sign up for email updates to stay up to date with all her posts. Dr. Schwartz is the author of four books:

Arielle Schwartz, PhD, is a psychologist, internationally sought-out teacher, yoga instructor, and leading voice in the healing of PTSD and complex trauma. She is the author of five books, including The Complex PTSD Workbook, EMDR Therapy and Somatic Psychology, and The Post Traumatic Growth Guidebook.

Dr. Schwartz is an accomplished teacher who guides therapists in the application of EMDR, somatic psychology, parts work therapy, and mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of trauma and complex PTSD. She guides you through a personal journey of healing in her Sounds True audio program, Trauma Recovery.

She has a depth of understanding, passion, kindness, compassion, joy, and a succinct way of speaking about very complex topics. She is the founder of the Center for Resilience Informed Therapy in Boulder, Colorado where she maintains a private practice providing psychotherapy, supervision, and consultation. Dr. Schwartz believes that that the journey of trauma recovery is an awakening of the spiritual heart.